Become a storyteller!

How to build the story with plots, characters, scenes…?

How do you bring the characters to life?

How to make the audience understand the action?

How to create a rich and complex world?

How to make the imaginary more real than real?

How to seduce the audience?

What message will the narrative deliver?

Many questions.

Only one answer: learn to tell.

Screenwriting course

Hello and welcome to Story&Drama, the site for storytelling in all its forms.

Almost all artists tell stories, but few really master narrative writing. To persuade you of the need to learn, I’ll first tell you a little about who I am and how I came to write this website and a whole collection of screenwriting courses, then tell you about storytelling in more detail, guiding you to the parts of the site that may help and interest you.

Story of a writer who teaches how to write

Literature or nothing

When I was 16, my life changed when I met the work of great writers: Arthur Rimbaud, Isidore Ducasse comte de Lautréamont, Stéphane Mallarmé, Fiodor Dostoïevski, Antonin Artaud, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, André Malraux, Marguerite Yourcenar, Marguerite Duras, Bernard-Marie Koltès, Bret Easton Ellis, Don De Lillo, etc.

Career as a published and award-winning writer

So I decided to become a writer myself.

5 years later I published my first book, then a second, a third, then 6 in all before 30 years. My first literary website was born in 1998 and was part of the first wave of the French web.

I collaborated for 3 years as a literary critic with a french magazine between 2002 and 2005.

I worked for 10 years on a 6-novel saga – my masterpiece, which I finally dropped because life brought me problems and other horizons.

Nevertheless, I continued to teach narrative writing and the art of screenwriting. In all, I spent 15 years writing full-time between 1995 and about 2010. Since then, I’ve continued to write, but on a dilettante basis – professionally I’ve moved into web writing and website creation at https://boutique-wp.fr/.

Literary Fellowships

In order to make a living by dedicating my whole life to writing, I applied for literary grants and won two of them: the Novel grant from the Centre National du Livre, in 2006, and the Mission Stendhal from the French Institute in 2008, which led me to settle in Berlin for 5 years.

Teacher of narrative writing

Narrative art workshops in Berlin

In Berlin, I developed my script training started in 2008 in Marseille: between 2008 and 2013 I taught in a few dozen workshops in English to a few hundred young international authors how to write narrative fiction, whatever the medium – book, comic, film, music, show, radio, etc.

It was while writing my novels in the 2000s that I began to systematically study the art of screenwriting, narratology, theories of narrative, stylistics, rhetoric, etc.

The Story&Drama collection of screenplay courses and analyses

After 2013, back in France, I wrote down my screenplay training, which became the Story&Drama eBook collection of screenplay courses in PDF.

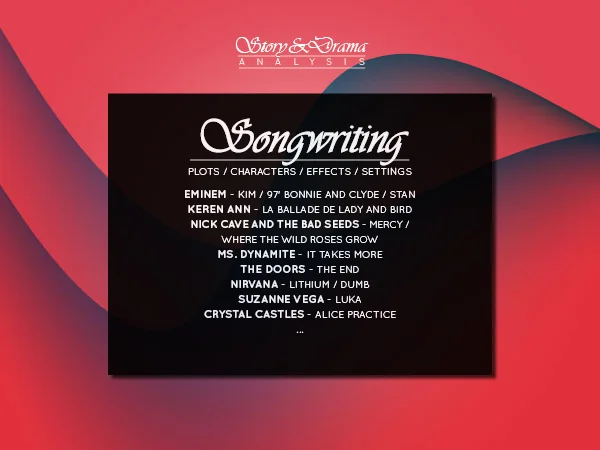

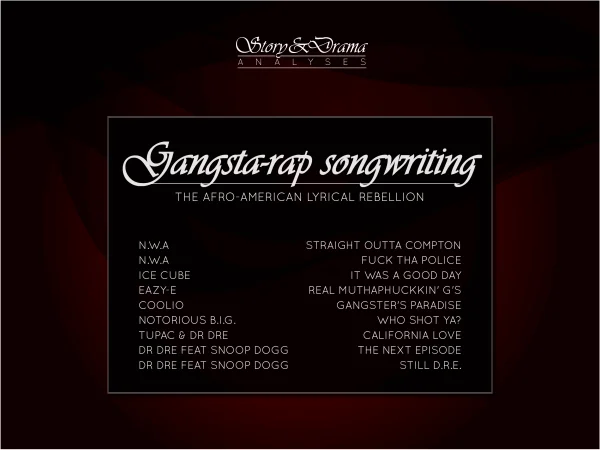

I completed these writing courses with a collection of analyses of famous works: the movies The Godfather and Pulp Fiction, the series Game of Thrones, the children’s story The Little Prince, the lyrics of 48 French songs and the lyrics of English songs, including gangsta-rap hits, 14 music videos, 12 comedy sketches…

The French version of Story&Drama now has 237 articles, the English one has 146 articles, and 3 other versions are available in German, Italian and Spanish.

What is the purpose of analyzing all these works?

First of all, to prove that the theory I teach works every time, regardless of the media, the genre, the style, the tone, the register, the themes, etc.

The theory I teach mixes elements taken from right and left: from the Russian functionalist Vladimir Propp, from the structuralist narratologists Greimas and Souriau, from the storytelling guru Robert McKee (whom I hate more than I like), and from a few other American script-doctors Blake Snyder, Linda Segers, who didn’t make much of an impression on me, but from whom I stole some minor ideas. You can find some of these influences in my blog, in the narrative theory section.

Enough about me and the genesis of my ideas, I’m now going to introduce you to the Story&Drama screenwriting course collection in more detail.

How to write a novel, a story, a comic book, a play, a movie, a series, a sketch, a song…?

Theory of narration

Putting the audience first

First of all, let’s be clear: I’m only talking to authors who are professional enough to understand that when you write a story, it’s not primarily to please yourself and scratch your belly button in front of everyone, but to please the audience.

I’ve had a lot of arguments about this with litanies of fake authors, who believe that as soon as they have the shadow of a bad idea, it’s enough to make it a work – the direct consequence is that such an attitude usually doesn’t lead to any work, and that even if there is a work, it hardly pleases anyone but its author. I don’t even call it art, it’s pure narcissistic masturbation.

Art, culture, are markets. The works in all the arts compete with :

- the thousands of masterpieces of the world heritage in all the media

- the thousands of works by professional and experienced authors in all media

So telling your little traumas or your vacation in Arcachon, in such a context, can never be competitive. Instead of spending hours reading a sloppy novel, reading a boring comic book or listening to an unfunny sketch, people will spontaneously go back to binging a great series on Netflix, a free doc on Youtube, or simply reread Rimbaud for the 12th time.

So if you don’t want to take the audience into account and put it at the center of your artistic process, if you think that it’s not necessary to work hard to develop a narrative work that is out of the ordinary, if you care more about yourself than about the cultural heritage of humanity, I have nothing to teach you – and I’m convinced in advance that we’ll never hear from you in art.

In all my teaching, therefore, I start from the fundamental principle that one must write FOR the audience, never without it.

Mastering the basics of narrative writing

All in all, from the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh to the Game of Thrones series, from chansons de geste to gangsta-rap or rock songs, through all eras and cultures, there is only one narrative, which consists in writing the history of mankind and the world.

The infinite variety of media, styles, genres, does not change the essence of things: just like the constants of the physics of the universe (gravity, Planck’s constant, the structure of atoms with protons and electrons), the constants of the narrative do not change. You absolutely need to know the terms and concepts of storytelling to write better stories.

Character and plot

The main character

So that a story is always :

- a main character

- who has a goal

- who meets obstacles

- and adversaries

- in the end the goal is reached or not

The identity of this main character takes, like Proteus, a thousand forms, a thousand faces:

- a mafia godfather

- a boxer

- a child from an asteroid

- a little girl

- a family, a clan

- it can even be a non-human character, a car, a cloud, an idea, a geometrical shape

But the fundamental structure remains intangible.

The plot

The fact that a hero is moving towards a goal generates a series of narrative steps, which we call the plot.

Here again, there can be at least 2 steps, or hundreds in a soap opera or a long series (this is precisely the glaring flaw of many popular series, which exhaust themselves adding steps to avoid the main character reaching the goal, twisting the golden goose of TV advertising).

There are 2 of them in the Paf the dog joke:

1/ It’s the story of a dog called Paf, he crosses the street (goal)

2/ and Paf, the dog (unexpected fall but programmed by the tragic name of the poor animal)

There are hundreds of them in Game of Thrones: the White Walkers take 8 seasons to attack, no less; Daenerys also takes 8 seasons to get out of her second role in Pentos to reach the heart of Lannister power in King’s Landing.

We have a few dozen in The Godfather: Michael Corleone, who starts out as an outsider with no role in the story, takes a few dozen steps to become the new number one godfather of New York, with the goal of replacing or even surpassing his murdered father.

We also have a few dozen steps in The Little Prince: the story of a child’s journey of initiation to discover the world and find a friend (whom he will eventually meet in the form of a fox).

The characters and the actantial roles

This main character, the Hero, rarely lives his story alone.

Here, the basic structure is to oppose an Antagonist to the Protagonist.

The Protagonist wants something, the Antagonist wants the opposite or the same thing that they cannot share:

- Michael Jackson’s character wants to scare his girlfriend, who wants to protect herself

- The little girl in the Skrillex video wants to take down the perverted pedophile man who wants to molest her

- Michael wants to avenge his father against the 5 families, who want to kill him

- The Baratheons then the Lannisters want to keep the power, the Stark and Daenerys, among others, want to take it from them

- Butch wants to finish scamming Marsellus and leave the city with the money he won by trickery, Marsellus wants to punish him and get the money back

- Ice Cube or his avatar in the song It was a good day just wants to spend his day as a gangster in a basically hostile environment

Around this central conflict other characters are organized, by affinity and alliance.

Protagonist and Antagonist thus surround themselves with partners, who, as the drama unfolds, end up forming teams, which then confront each other in a series of duels, or in a collective struggle, sometimes massive (this is what we observe in many stories that first spend time accumulating individual conflicts, before organizing a long final collective battle: in Westerns as in Star Wars, in war films as in ancient or medieval epics).

A story that tells stories

A number of types of works tell only one plot: the story is reduced to a single story.

Thus, most of the time, a joke, a short children’s story, a song, a video clip, tell a single plot. In 5 minutes the main character reaches his goal or not, the audience knows the result, the suspense does not last long.

But the pinnacle of screenplay art is reached by those narrative cathedrals that are novel sagas, epic series, film-frames, in short: complex narratives, which can tell hundreds of intertwined plots.

These stories involve multi-faceted characters, engaged in dozens of plots and playing very different dramatic roles.

In Pulp Fiction, for example, Marsellus can be a mentor in one plot, a protagonist in another, and an antagonist in a third. Vincent plays the role of a killer in one storyline, commissioned by Marsellus to kill some kids, and the role of a lover in another storyline where he ends up sleeping with Mia, Marsellus’ wife.

Similarly, in Michael Jackson’s video Thriller, his character plays paradoxically opposite roles: persecutor of his girlfriend in one plot, protector of her in another.

In the best complex stories, the same characters play both major and minor roles in different plots; this diversity brings richness and realism, verisimilitude and nuance.

Storytelling courses

Introduction to Storytelling

In my Storytelling – Introduction, designed for all audiences but especially for beginning writers, I lay the groundwork for screenwriting: defining character, actantial roles, story and plot, acts, and a brief introduction to dramatic effects and narrative parameters.

Working Method

In the Storytelling – Working Method, I outline the steps in scriptwriting that I believe are necessary. Research and documentation first, character and plot development second, general editing, and finally writing (a long process of writing and rewriting).

Storytelling course 1

In this beginner’s screenwriting course, Storytelling – 1. Beginner, I lay out the basic rules outlined in Introduction to Storytelling, but in much more detail.

We discover the difference between thematic and actantial roles for characters, and I introduce the various types of editing. I say a little more about dramatic effects and narrative settings and introduce the notion of narrative information distribution.

Screenwriting course 2

Intended for more experienced writers, this screenplay course – Storytelling – 2. Advanced – builds on the content of the first course, but goes into greater depth and complexity to satisfy the need for knowledge of ambitious writers.

We study the problem of dividing a story into scenes and sequences, the problem of transitions between plot fragments, we detail the narrative parameters (media, genre, tone, register, style…), we analyze the possible effects of chronology and we observe how the same narrative structure can be told in different ways by varying the narrative voices, the focus, the point of view of the narrator (omniscient or embodied) etc.

We also develop the question of the distribution of narrative information among the characters and to the audience.

Script analysis

Theory is great, because a good artist has good ideas in his head, and more than ideas: creative tools, operating concepts.

But for us authors, the only thing that really counts is our work, the product of our imagination.

So I have undertaken a gigantic exercise of applying the ideas, concepts and tools of my screenwriting classes to dozens of very different works, to show concretely how it works, how it is done, how screenwriters and narrators get their message across, bring their characters to life, manage dramatic tension, play out the values between their characters, etc.

The objective is to learn screenwriting by watching the masters of screenwriting in all the arts, film writers, TV writers, comedy writers, lyricists, video writers, writers…

To analyze their works, to study their writing techniques, and to be inspired by their know-how.

In each work, I tried to go far in the analysis, to reconstitute all the plots, to list all the characters and their thematic and actantial functions, to comment on the narrative and dramatic effects used, and also to underline the stylistic effects, by which the deep structures of the narration and the meaning take shape as words, sound, images.

Film and series scripts

In Pulp Fiction, I found 10 plots, 30 actantial roles, a big thematic work on the symbolism of places and various other themes (drugs, food, scatology…)

In The Godfather, I counted 15 sequences telling a total of 27 plots, with about 100 actantial roles attributed to several dozen characters structured around the protagonist, Michael Corleone.

In Game Of Thrones, of which I analyzed the first 2 seasons, that is to say 20 episodes (the series was on air when I wrote the analysis) counting about 410 scenes, I counted more than 100 plots, with 67 characters taking a total of 174 actantial roles.

Novel scenarios

In search of a novel known to an international audience, I decided to analyze The Little Prince since this book is THE worldwide literary success – it has been translated into dozens of languages and is known all over the world.

In its 27 chapters, page after page, I found 25 plots, with 17 characters sharing 54 actantial roles – the Little Prince alone takes on 27, or half of them. This is normal, since most of the plots, told from the child’s point of view, are duels between the naive but intelligent child and a half-crazed adult.

Thematically, however, I denounced the sexism of this admirable tale, full of magic, but which assigns strictly no actantial role to women.

Song and music video scripts

I analyzed the lyrics of dozen pop, rock and rap songs, and a dozen west-coast gangsta rap hits.

Case by case, I found a different narrative art, sometimes even almost absent: some songs simply rely on something other than narration, or on incomplete and attenuated forms of narration.

In Gangsta rap lyrics, I’ve generally found them to be more discursive than narrative – a big mix, let’s say. Thugs often have better things to do than write a narrative. Still, there are big chunks of narrative floating around in the rapper’s soup – like when NWA taunts the cops in Fuck tha police, and tells them all about the trouble they’re going to get into.

Similarly in Music Videos: some tell a real complex story, such as the legendary Thriller video, which tells 7 brilliantly interlocking plots; others, such as Sebastien Tellier’s Look video, use a poetic and thematic form of storytelling (we are told about changes in mood and emotion).

Conclusion

So that’s the kind of screenwriting course and training you’ll find on this site.

I hope it will inspire you and stimulate your screenwriting creativity and narrative imagination to reach new heights of fictional power!

Feel free to leave a comment if you have any comments or questions.

And if you appreciate the content of this site, please link to it from your blog or website, it’s always nice to be read 🙂