Story, by Robert McKee

A seminar, then a book

In 1984, Robert McKee began teaching storytelling in a seminar called Story at the University of South California.

In the decades that followed, he offered his teaching in the form of a 3-day seminar in many cities of the world: Los Angeles, New York, London, Paris, Sydney, Toronto, Boston, Las Vegas, San Francisco, Helsinki , Oslo, Munich, Tel Aviv, Auckland, Singapore, Barcelona, Stockholm, São Paulo… Robert McKee would have been followed by more than 50,000 people.

In 1997, the Story seminar became the book Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting.

It should be noted that Robert McKee, who teaches how to write a film, was only once the author of a film produced; he sold scripts to studios, who ultimately did not produce a movie with them. Without taking anything away from his teaching, this fact makes it clear that McKee is a successful teacher, not a successful screenwriter. Neither artist nor researcher, he popularizes with a certain talent.

The chapters of Story

Story consists of the following parts and chapters:

Part one: the screenwriter and the art of storytelling

- Introduction

- The problem of the story

Part two: the elements of the story

- The spectrum of the structure

- Structure and setting

- Structure and genre

- structure and characters

- Structure and meaning

Part three: the principles of the narrative form

- The content of the story

- The triggering incident

- The conception of Acts

- Scene design

- Scene analysis

- Composition

- The crisis, the climax and the resolution

Part Four: The Screenwriter at Work

- The principle of antagonism

- The exposition

- Problems and solutions

- Characters

- The text

- The author’s method

First remark: here is a plan which contains some oddities …

Indeed, the chapters on the triggering incident, the crisis, the climax, the resolution, and the exposition, are scattered over 2 parts, while all these concepts belong to the classic plan of a plot; furthermore, McKee quotes them out of order, the logical order being: exposition, triggering incident, crisis, climax, resolution.

In addition, two chapters of the fourth part (the principle of antagonism, and the characters), relate to the characters but are disjointed; and two chapters in part three and four (scene design, and text) deal with writing. It would have been more logical to group these chapters into some parts called “the character” and “the writing”.

Also, the chapter on antagonism should logically belong to the third part since antagonism is a “principle of the narrative form”.

It sounds like details, but it’s telling about McKee: a somewhat messy mind.

Commented summary of Story

In this part, we will both summarize Robert McKee’s Story, and comment on his point.

Part one: the screenwriter and the art of storytelling

Introduction

McKee sets out his intentions:

“Story presents principles and not rules”.

“Story is about eternal and universal forms, not formulas. ”

“Story is about archetypes, not stereotypes. ”

“Story insists on the requirement for precision and the refusal of shortcuts. ”

“Story deals with the realities of writing, not its mysteries. ”

“Story explains how to master this art, not how to predict market reactions. ”

“Story incites respect and not disdain towards the public. ”

“Story encourages originality and not reproduction. ”

1. The problem of the story

Robert McKee notes the importance taken by storytelling in contemporary life, audiences being showered with stories of all kinds in various media, but he laments their general and critical mediocrity including Hollywood. The Writers Guild of America is said to record 35,000 screenplays each year, of which only a handful are of high quality.

McKee therefore recommends learning scriptwriting like any demanding art. He recounts his experience as a script reader and regrets the general weakness of the narrative design. He takes the example of two bad scenarios, one too anecdotal, the other too spectacular, both incapable of telling a good story.

Part two: the elements of the story

2. The spectrum of the structure

The life of a character is a long series of facts in which the screenwriter must retain only the best. That is, “events” that change “values” – a value (not in a moral sense) being some kind of core of meaning such as love / hate, life / death, wisdom / stupidity etc. McKee states that a standard movie has between 40 and 60 “events”, a novel 60 or more, a play about 40.

These events are the foundation of the scenes – a scene must necessarily deal with an event, a change of state of the value. These changes take place through “highlights” which punctuate the scene.

The “sequences” are coherent sequences of scenes. McKee cites a 3-scene sequence whose values range from self-doubt to confidence, from confidence to defeat, and from social disaster to triumph.

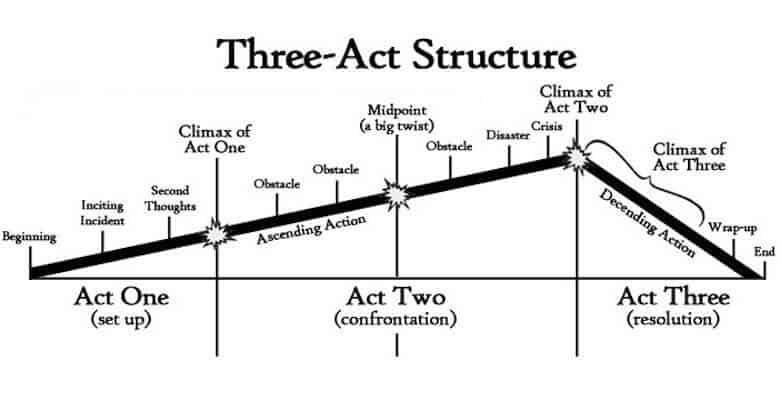

An “Act” is a series of sequences which culminates in a climax scene which overturns values in a significant way.

A “story” is a series of Acts – and the sequence of changes in value forms the “dramatic arc” of the story. This series of Acts evolves towards a climax of the Last Act, a major and irreversible change.

Note: McKee did not invent any of these concepts, the origin of which goes back to Aristotle through structuralism – authors he hardly ever mentions except in his bibliography. But he makes it a synthetic and interesting presentation.

McKee then presents a concept that he seems to have created and that seems very obscure to me: the triangle of plots. A plot would be made of one form or another among 3 types of plots: Archplot, Miniplot, Subplot.

The Archplot would fit the classic pattern of narratology and have a closed ending, an active protagonist; the Miniplot would be a minimalist variation and would have an open ending, a reactive protagonist; and the Subplot would be an nonconformist form of plot with a non-linear unfolding.

In my opinion, this is where we see McKee’s intellectual limits… he explains well what we already know but when he wants to innovate, it sometimes becomes rubbish. As an analyst of dozens of stories, I do not find his classification relevant and he does not put forward much evidence. McKee nevertheless defines his 3 types of plot with 7 interesting oppositions:

- closed or open end

- external or internal conflicts

- one or more protagonists

- active or reactive / passive protagonist

- linear or non-linear temporality

- causality or coincidence

- consistent or inconsistent realities

To add to the confusion, McKee adds a 4th type, the non-plots – static plots without a dramatic arc.

Suddenly it is difficult to see why this choice of the “triangle”: McKee simply presented 4 possible types of plot.

McKee then debates the connection between his plot types and commercial success: the Archplot is obviously the most commercial, and the Subplot is the riskiest.

3. Structure and setting

“The setting of a story has 4 dimensions: time, duration, place and the intensity of the conflict”. The intensity of the conflict lies in “political, economic, ideological, biological and psychological forces”.

McKee recommends limiting the size of this “setting”. To determine this, he advises using memory (your recollections), imagination, and facts (documentation, eg books on a given topic).

4. Structure and genre

McKee briefly reviews the genre theorists: Aristotle, Goethe, Norman Friedman… He then tries to list the genres:

- Love story, or friendship story

- Horror

- Modern epic

- Western

- War

- Maturation / coming of age

- Redemption

- Punitive plot

- Test plot

- Educational plot

- Disillusionment plot

- Comedy

- Crimes (sub-genres: criminal mystery, criminal story from the point of view of the criminal, gangster story, police officer story, thriller, revenge, court, spy, prison, film noir…)

- Social drama (subgenres: domestic drama, women’s film, political drama, economic or ecological drama, medical drama, psychodrama)

- Action or adventure (sub-genres: war drama, political drama, great adventures, disaster / survival)

- Historical drama

- Biography

- Docudrama

- Pseudo-documentaries

- Musical film

- Science fiction

- Sport

- Fantasy

- Art film

Notes:

First it is unfortunate that McKee only talks about films since obviously genres cross the media (we can make SF in comics, books, films etc).

In addition, this list has a frankly messy and confusing side, and puts very different types of genres on the same level. For example, the cartoon is not a genre, it is a form of media. Science fiction and drama are not two distinct genres, they are two different categories, SF is a kind of world (like the western) in which comedies as well as psychodramas or political dramas can take place, which belong to the same category: they are kinds of action. The love story is not a genre, it is a possible theme for a plot.

In fact McKee is dealing with a subject he has not bothered to master.

However, it is not that complicated if we want to understand something: it suffices to distinguish different parameters (the medium, the type of world, the type of dynamics of the story, the type of theme, the tone (comic, serious… )) and differentiate between genres on this basis.

McKee then revisits some of these genres, which he sees as stimulating creative constraints.

5. Structure and characters

McKee first distinguishes two concepts:

- the characterization (all properties of a character: age, gender, etc. appearance)

- and the character, which he defines as the choices a human makes under pressure.

Note: it does not start too well since some of the infinity of possible characters are not human: a dragon, an elf, a virus, a hurricane, a vampire, an alien, a haunted house, cancer… have neither human characterization nor human character. Linda Seger in her book on the characters falls into the same trap (before correcting herself moderately). If you want to understand the narrative well, use the structuralist concept of AGENT instead (from the narrative scheme and the actantial scheme) : a character is an agent, a being who acts, period; whether it is a human, an imaginary being or a thing does not change the matter: the character is defined by its dramatic function, all the rest is just chatter and confusion.

McKee then states: “The function of the structure is to provide progressively increasing dramatic pressures which force the characters to face increasingly difficult dilemmas (…) The function of the character is to bring to the story the qualities of characterization necessary to make the choices in a truly effective way”.

Then he recommends working particularly on the final climax, which gives the character all his dimension (he’s talking about the Hero, not all the characters).

6. Structure and meaning

McKee first develops the idea of aesthetic emotion, “the simultaneous meeting of thought and sensation”, on which the story should be based.

Then he says that a story is also the expression of a thought and therefore has a rhetorical aspect: “Telling a story is a creative demonstration of the truth. A story is the living proof of an idea and the transformation of an idea into action. The event structure of a story is the means of expressing and then proving an idea… without explaining it”.

There, for once, I salute McKee, for he is one of the small number of authors who have understood that a story is not worth much if it does not have deep meaning.

Then McKee introduces the concept of guiding idea: ” The guiding idea can be expressed in a single sentence describing how and why life undergoes changes from one condition of existence at the start of the film to another at the end of the film. ”

He recommends basing the guiding idea on a value (as before: a large element of meaning, such as justice, freedom, life, etc.) and a reason, a logic. He gives as examples: the guiding idea of Columbo would be “Justice triumphs because the policeman is smarter than the criminal”, while the guiding idea of Dirty Harry would be “Justice triumphs because the policeman is more violent than the criminal ”.

Robert McKee classifies guiding ideas into 3 types: idealistic, pessimistic, and ironic. All 3 go through strong positive and negative times, but: the idealist starts with the negative and gradually goes up to the positive; the pessimist begins with the positive and gradually sinks into the negative; and the ironic does both at the same time.

Part three: the principles of the narrative form

7. The content of the story

Note: another illogical choice from Robert McKee: this chapter will only talk about the protagonist, while he announces that he will talk about the story…

McKee begins by asserting that the substance of narrative art is intangible, then he says that it can only be accessed through the protagonist.

He evokes the case of multiple protagonists (eg The 12 bastards ), and the case of non-human protagonists.

He defines the protagonist as a character who has will and a conscious or unconscious desire, and who is able to carry this desire to the end. He must also inspire empathy (even if he is a monster).

McKee represents the protagonist in 3 concentric circles linked to 3 possible levels of conflict:

- internal conflicts within the inner self, with body and mind

- personal conflicts, with the lover or the family

- extra-personal conflicts with society or the physical environment.

These conflicts are manifested in the “narrative gap” that exists between the protagonist and the object of his desire. This desire carries risks – which are a measure of the value of the object of desire. The more valuable the object of desire, the more difficult it is to reach and the more risks must be taken to cross the narrative gaps.

8. The triggering incident

McKee begins by developing uninteresting digressions, then finally tackles his subject.

The triggering incident turns the life of the protagonist upside down – positively or negatively. For example in Jaws , when the shark attacks its first victim.

The protagonist must react strongly to this incident; from there, he formulates a desire which will form the “spine” of the story.

The public can automatically imagine possible resolutions – during the crisis and the climax: either the desire is satisfied or it is not. In Jaws , the protagonist wants to kill the shark and we can imagine in advance whether he will succeed or not.

This incident must be shown in the first quarter of the film, according to Robert McKee (who here totally confuses the story and the plot: in the case of a multi-plot film like Pulp Fiction, the idea of McKee is just inapplicable). Then he cites several examples that contradict the advice he just gave…

9. The conception of Acts

From the triggering incident to the climax, the plot must pass through a series of “points of no return” in a crescendo progression that goes from conflict to conflict.

Depending on the size of the story, we will do 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 Acts. Each Act has its progression and its climax.

If the story consists of multiple plots, the subplots have fewer Acts than the main plot, and all of those Acts are intertwined in a general composition.

McKee then evokes a number of possible articulations between the plots.

10. Scene design

McKee defines the scene as a story in miniature, in which the values at play change substantially. A scene must of course follow the backbone of its plot, and therefore advance the action from the triggering incident to the climax.

11. Scene analysis

Robert McKee exposes an interesting distinction between text and subtext: there is what things look like – for example, a man changes a tire to help a woman – and what is really going on in depth – for example, the man and the woman feel attracted to each other. Their dialogue speaks of the tire while the stake is love.

McKee then presents a scene analysis technique:

- define conflict – the driving force behind the scene

- note the value in the opening and its emotional charge

- split the scene into dramatic highlights

- note the value in the end and compare it to the opening value

- spot the highlights and locate the dramatic pivot

12. Composition

McKee recommends paying attention to the rhythm of the scenes – therefore to their lengths which must vary – and to their tempo – slow or fast.

He then presents 4 ways to advance the story:

- social progression: we open up to a small number of characters, and the action leads to widening the field to integrate new ones

- personal progression: opening up to a personal or internal conflict, then progressing towards psychological, moral, emotional complications

- symbolic progression: going from the particular to the universal, from the specific to the archetypal, from the insignificant to the symbolic

- the ironic progression: the character arrives right where he did not want to go, or moves away from the goal he was doing everything to reach

13. Crisis, climax and resolution

“The crisis is the third phase of a five-phase form.” It derives directly from the triggering incident, which opened up the prospect of a confrontation between the protagonist and an antagonist. It represents a dilemma, a difficult choice to make.

The crisis leads to the climax, the fourth phase, which is the moment when the story changes definitively.

The climax leads to the resolution, fifth phase, which shows the consequences of the climax, a new situation.

Part Four: The Screenwriter at Work

14. The principle of antagonism

Antagonism is a fundamental principle of storytelling; the public’s interest in the protagonist depends directly on the level of antagonism they face.

Robert McKee then exposes a very interesting tool, of which he is probably himself the author; he recommends to

- choose a value – for example Justice

- then find it a contrary value – for example Injustice

- then a contradictory value – for example Illegality

- then a negation of the negation – for example Tyranny

These values then become stages in the protagonist’s struggle against antagonism.

15. The exposition

First Robert McKee recalls the famous principle: “show, do not tell”. The public needs to understand the information without being told. For example, don’t have a character say, “oh, are you a high-ranking Nazi official?” But show a man arriving in a fancy swastika-branded car with a driver, and when he gets out we see his handsome Nazi uniform being saluted by the others.

McKee says there are only two ways to turn a scene around: by action, or by revealing information.

A past story is a way to reveal information; the past story, which concerns the past facts of the current story, can be told during that story, through dialogues, or through flashbacks.

A voiceover can also reveal elements of the exposition.

Note: McKee makes very special use of the exposition concept, as he cites examples of expositions at the end of the story. This is not the classic definition: normally, an exposition takes place at the very beginning, it presents the world, the characters, the genre.

16. Problems and solutions

Here Robert McKee lists 8 common problems to which he provides solutions:

- The problem of interest

- It is resolved by arousing curiosity and concern.

- The problem of surprise

- We must avoid mediocre surprises and give preference to genuine surprises, those which “spring from the sudden revelation of the gap between expectations and the result”.

- The problem of coincidence

- We must avoid those that come and go immediately, and even more avoid using them in the climax.

- The comedy problem

- McKee recommends focusing on the dark sides of life, the negative, because that’s what we laugh about. We must also multiply the dramatic pivots and comic surprises.

- The problem from the point of view

- The same facts can be seen from different points of view. You have to try to follow the protagonist’s point of view, otherwise you lose tension.

- The problem of adaptation

- Each medium has its strengths and weaknesses. The strength of theater is dialogue. That of the novel is the text. That of cinema is the image. Conflicts are therefore not expressed in the same way at all.

- The problem of melodrama

- Melodrama is a weakness to be avoided. For that, you need characters who follow through on their actions.

- The problem of narrative holes

- Causal breaks and logic errors must be avoided. At worst, we can point them out the better to make them forget.

17. The characters

The character is defined by a desire, conscious and unconscious, a motivation, and strong actions. Its complexity comes from its contradictions between opposing characteristics.

All the characters must be defined in relation to the protagonist. They bring out its contradictions. For example a woman brings out the protagonist’s tender and cruel sides, a rival brings out his kindness and wickedness. When they are close to the protagonist, they must remain complex. If they are far apart, they can be simpler.

18. The text

Robert McKee deals first with dialogue, which must be concise and have strong direction.

In cinema, he recommends using symbolic “image systems” – because the best way to make sense is visual. For example, the film Casablanca uses a system of images linked to the prison: blinds, banisters, leaves, make shadows that resemble prison bars.

19. The author’s method

McKee first presents a badly written story with no future: improvised without a plan, with good moments, but without powerful dramatic structure, therefore good for the trash.

Then he gives a method to properly conceive the story:

- Write on index cards, do “a bunch per act”, then destroy 90% of it when you have discovered the right narrative climax, to keep only 40 to 60 scenes. A good story should be ready to be told step by step in 10 minutes.

- If this story is validated, develop a longer “treatment”, where every detail of the scenes works.

- If it is validated, all you have to do is write the scenario – ending with the dialogues.

Critical review

Arguably the most famous screenwriting manual, Story has qualities as great as its many flaws:

- Story gives an interesting and at the same time sketchy exposition of classic plot theory; he hardly ever cites his intellectual sources; it presents the elements of a typical plot in disarray and in a broken fashion, which makes it difficult to assimilate; he sometimes confuses the story and the plot, or speaks of the character when he actually designates only the protagonist

- Story doesn’t clearly define how one builds a full system of characters, it mostly deals with the protagonist and his allies, but speaks little of the other side; and McKee talks about the characters in different and distant parts: it would have been better if he devoted a complete and logical part to this vital concept

- Story brings some innovative and very interesting techniques: this is the case with its technique of value systems, or the technique of writing scenes, or its part on the subtext, or even the decreasing complexity of the characters as we move away from the protagonist

- Story mentions numerous examples – but almost all of them are borrowed from the cinema, more rarely from the theater, never from literature or music; yet a whole part of his ideas can easily be applied to other arts

- Story is very incomplete concerning the mixture of plots – at most it only deals with a story with 3 plots – it is quite unable to explain the structure of Pulp Fiction which has 10 plots, or of the Thriller clip which has 7 plots

- Story is sometimes confused and vague, it deals with a subject without being able to conclude anything from it: a few vague intro paragraphs, then a series of examples, and you wonder what he really meant

- Story offers some frankly wobbly theories: its presentation of genres is very incomplete, and its theory of the 3 types of plot does not stand

Still, Story remains a book to know, because its best parts really add something to the authors. Even when you find it wrong, reading its 380 pages is sobering.

Personally, reading Story when I was a novelist took me a step forward in my story design. Later, when I took to teaching storytelling, I fed on better sources, and the flaws in Story became clear to me. Nevertheless, it has been an essential stage in my development as an artist and teacher.

So authors, here is my advice: read Robert McKee’s Story, assimilate it well, then go beyond it, in particular by reading structuralist narratology (Greimas, Souriau, Jean-Michel Adam etc), more universal, more intellectually demanding, and stronger on the theoretical level.

Bonus: Robert McKee’s official website