In a nutshell

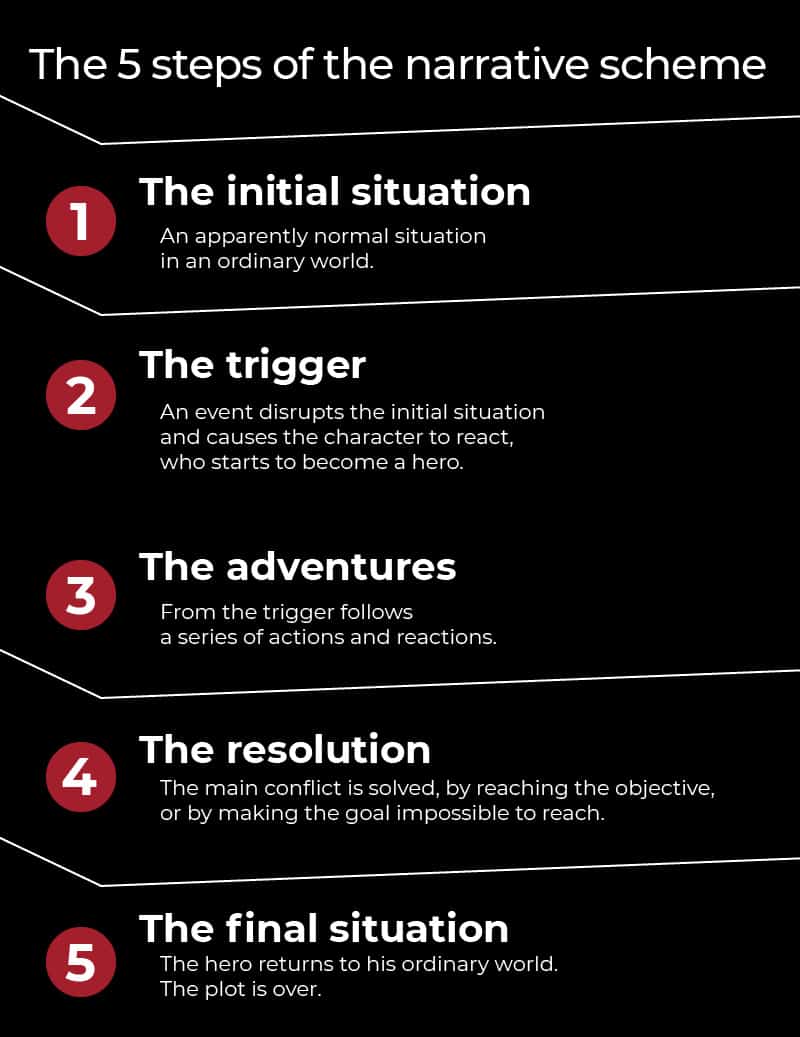

The narrative scheme is this:

The 5 stages of Algirdas Julien Greimas’ narrative scheme

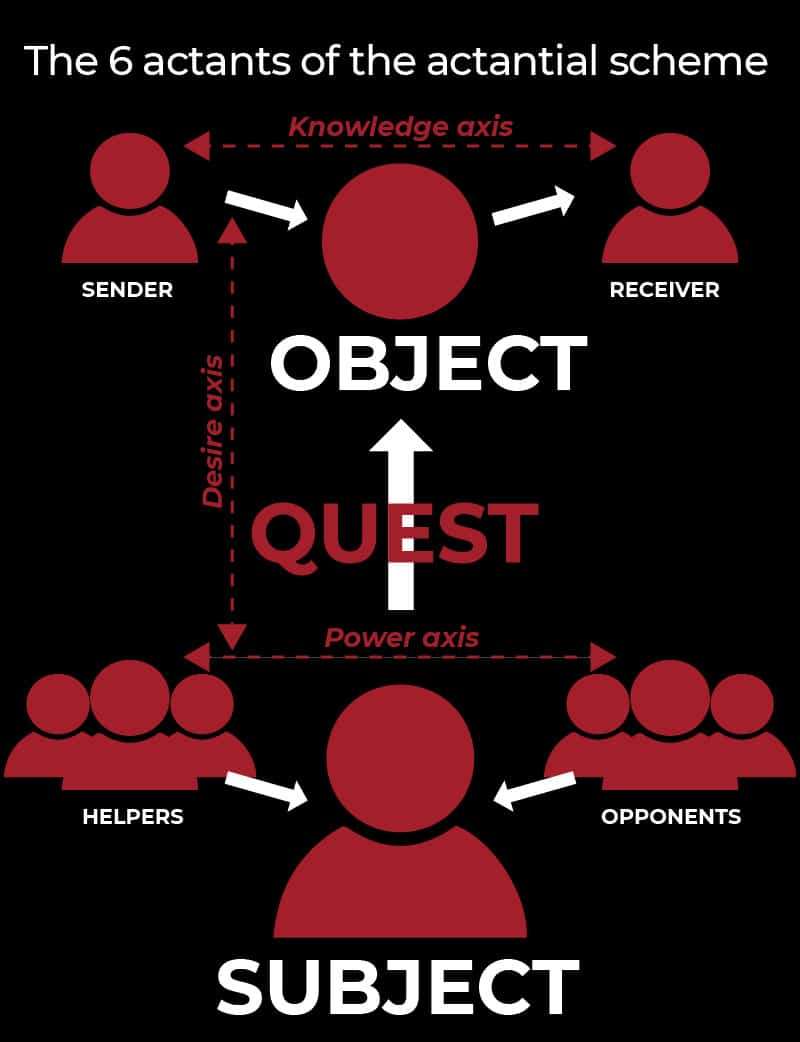

The actantial scheme is this:

Greimas’ actantial scheme

I have taken up these two concepts, simplifying and universalizing them even more, in my screenwriting course series and in my analyses.

Now, would you please take a few more explanations to better understand what they are about?

Two great tools for writing and analyzing stories

From Aristotle to Polti, Propp, Souriau and Greimas

For 2300 years, the old theory of the philosopher Aristotle (the “poetics”) served as the only frame of reference for narrative analysis, which was almost non-existent.

Then suddenly, narrative analysis was profoundly renewed in the 20th century with authors such as George Polti, Vladimir Propp, Etienne Souriau and Algirdas Julien Greimas.

These four founders of modern narratology all agree that there are deep structures of narrative at work in all the stories of the world.

In his book The 36 Dramatic Situations, George Polti takes up an old idea of Gozzi’s, who states that any story can be reduced to one of these 36 situations, such as: Making a fatal mistake, Avenging a crime, Solving a riddle, etc.

Ironically, Etienne Souriau took up the idea 50 years later by proposing The 200,000 dramatic situations.

In his book The Morphology of the Tale, Vladimir Propp studied hundreds of Russian folk tales, and showed that they always had the same structures:

- 31 narrative functions – think of them as the unknowns in a long equation, like x + y -z = a / b, etc.

- 7 character types: Hero, Princess, Villain, etc.

The narrative analysis of Algirdas Julien Greimas

The linguist and semiotician Algirdas Julien Greimas (1917-1992) took up and developed Propp’s ideas in the 1950s, reducing the number of narrative functions and character roles and universalizing the demonstration.

Greimas thus defined:

- A narrative schema in 5 stages

- An actantial scheme in 6 roles

Since then, his analysis tool has become a reference, both in the academic world and among narrative creators.

Narrative analysis? Yes: we analyze stories to better understand them, but also to better create them!

A physics-chemistry of storytelling

Narrative analysis can be compared to physics and chemistry: once we understand how matter is made, we can better manipulate it. In the same way, when we understand that all the stories in the world, in all genres and all media, are made of the same elements, we know how to tell better.

Narrative theory is therefore of interest to students and teachers who study works of literature in particular, as well as to narrative artists of all kinds, in literature (novels, short stories, poetry), in music (song lyrics), in comics (comic book scripts), in cinema and television (film and series scripts, but also documentaries).

Let us now see what these two essential schemes are made of.

Narrative scheme and actantial scheme: two sides of the same coin

Just as there is no plot without a character and no character without a plot, there is no narrative scheme without an actantial scheme.

Note this: we are talking about plot, not story, because a story can include dozens of plots. For example, I counted 27 plots at work in the film The Godfather.

A plot can be defined as a series of actions performed and experienced by a character in the position of a hero.

The narrative scheme is a universal model of plot structure.

The actantial scheme is a universal model of the functions and relationships of characters in a plot.

Now consider them in detail.

Definition and examples of Greimas’ narrative schema

Greimas’ narrative scheme designates a coherent succession of actions, performed or undergone by the same character, and which are logically linked, leading from a beginning to an end.

Here are the 5 stages of the narrative scheme:

| 1. Initial situation | A seemingly normal situation, which may be static or dynamic, in an ordinary world. |

| 2. Trigger or disruptive element | An event disrupts the initial situation and causes the character to react and become a hero.

This step introduces dramatic tension and sets a goal that steps 3 and 4 will have to resolve and achieve. |

| 3. Adventures | From the trigger, a series of actions and reactions follow.

The Hero joins forces with other characters and faces opponents who stand in the way of his goal. |

| 4. Resolution | The events lead to the beginning of a return to normalcy by resolving the main conflict, by reaching the objective defined in the trigger, or by making the objective impossible to reach. |

| 5. Final situation | The hero returns to his ordinary world. The plot is over. |

Examples of narrative schemes

The TV monster and the child

| 1. Initial situation | A child watches a cartoon on TV, a story about monsters. |

| 2. Trigger or disruptive element | A friend of the monster suddenly disappears. The monster panics, gets out of the TV, sits down next to the child, and asks for help to find his friend. |

| 3. Adventures | The monster takes the child into the world of TV where they have a series of wonderful adventures in search of the missing friend. |

| 4. Resolution | The child succeeds in finding the monster’s friend. |

| 5. Final situation | The child bids farewell to the monster and his friend, gets out of the TV, and finds his parents with whom he acts as if nothing had happened. |

Asterix and Obelix against the Romans

| 1. Initial situation | Asterix and Obelix are picking mushrooms in the forest. |

| 2. Trigger or disruptive element | The Romans arrive near the Gaulish village and their presence worries Asterix and Obelix. |

| 3. Adventures | The Gauls declare war on the Romans, and a series of conflicts and battles follow. |

| 4. Resolution | Asterix and Obelix beat the hell out of the Romans, who decide to leave the area. |

| 5. Final situation | The Gallic village organizes a banquet to celebrate the departure of the Romans. |

The jogger and the kidnapper

| 1. Initial situation | A woman is jogging in a park. |

| 2. Trigger or disruptive element | A man bursts out of a bush and blocks the jogger’s path. |

| 3. Adventures | The man kidnaps the woman, who discovers that the kidnapper is a childhood friend of hers who was hurt, and who seeks revenge. |

| 4. Resolution | The woman convinces the kidnapper to forgive her and release her. |

| 5. Final situation | The kidnapper ends his life and the jogger returns home, distraught. |

Definition and examples of Greimas’ actantial scheme

Another of Greimas’ creations, the actantial schema (or actantial model) describes the functions that the characters and anything else capable of playing a role assume during the five stages of the narrative schema.

The basic structure is: a subject, the Hero, goes in search of an object, the goal of the plot.

Example: a boxer wants to win a fight, humanity wants to survive an alien invasion, a man wants to win a woman’s heart, a woman wants revenge for a crime, etc.

This quest can be motivated by other characters, which Greimas calls :

- the sender or destiner (whom I call Mentor in my classes), who motivates the Hero to pursue the goal

- and the recipient, who is the beneficiary of the quest.

Example of sender: the king sends his son to kill a dragon, the king is the sender.

Example of recipient: a woman robs a bank to pay for expensive treatment for her seriously ill husband, recipient.

The subject can be helped by characters that Greimas calls “adjuvants”, and is opposed to other characters, the “opponents”.

Example: in Asterix and Obelix, Dogmatix and Getafix are often adjuvants, and Caesar, the centurions, and the Romans in general, are opponents.

Note: any being, even an inanimate or abstract one, participating in the action is considered a character: a magic sword, a car, a storm, fear, love, can thus be adjuvants or opponents by playing a role in the hero’s adventure.

Greimas differentiates between actants, which are functions that beings can take on, and actors, which are these beings. Thus, the same actor can play the roles of different actants.

Example: the same traitor character is first allied with the Hero before siding with his adversary. This actor occupies two functions as an actor.

Or, the same character can be his own opponent, and simultaneously occupy two functions as an actant.

Greimas also establishes three axes of relationship between the beings in a plot:

- The axis of will or desire links the subject to the object.

- The axis of power opposes the adjuvants and the opponents.

- The axis of transmission or axis of knowledge links the axis of will to the addressee and the addressee.

- Narrative scheme + actantial scheme

When we link the two diagrams, we understand each other better:

- First, we have the initial situation, in which the plot will take shape. No actant is defined.

- The triggering element defines the axis subject => object, gives a goal to the character who becomes a Hero (sometimes with the support of a transmitter).

- The adventures see the Hero surround himself with adjuvants, meet opponents, and work towards the object of the quest.

- The denouement is the moment when the subject meets the object or loses it definitively.

- The final situation concludes the plot by bringing the object or its loss back to the destroyer and/or the recipient.

Conclusion

I hope this article has taught you something.

If you are an author, writer, or narrator, I highly recommend using these two very powerful tools to craft your stories and characters.